Was Jean Laffite a Marxist? I don't think so. I think he was a self-made wealthy person who believed in free enterprise, and who had a keen sense of the importance of property ownership. Reading his letter of protest to James Madison, you can see how pained Laffite was to have his property confiscated by the United States government. Jean Laffite kept his money in a Swiss bank, divided it equally between the children of his two wives upon his death, and in all other respects followed the laws of contracts when divvying up the spoils on his privateering ships.The owner of the vessel was always paid a much larger share than the lowliest crew member, but each was paid a percentage of the take. Obviously property ownership was important to Jean Laffite, and he rewarded people based on their material contributions to the success of his ventures. He also donated money to causes he believed in, among them the liberation of slaves; and he took great pride in being able to do so.

But could Laffite have supported Marx financially, as is suggested by some sources? I think that is entirely possible, given that what Marx may have said when he was young and how it is interpreted today are two different things.

Young Karl Marx is to be distinguished from old Karl Marx. To read some English translations of Young Karl Marx's works, you might want to follow this link:

http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_Young_Marx.pdf

Could such an idealistic and ambitious young man have caught the eye of the aging Jean Laffite as someone whose cause was worth supporting?

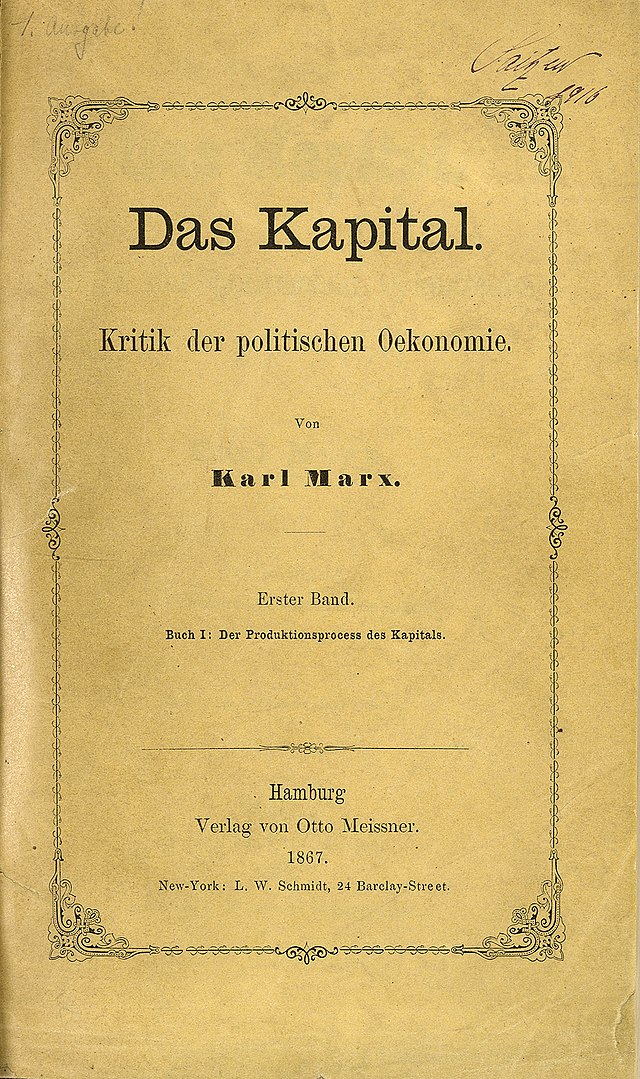

Confession: I have not actually read

Das Kapital. I am also fairly sure that neither had Jean Laffite before he died, because this magnum opus by Marx was not published until long after Laffite's death. But even if portions of it were available while Jean Laffite was alive, I am pretty sure he could not have read them, as they were in German.

If you would like to try reading it,

Das Kapital can be found free online here:

http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nnc1.cu56552327;view=1up;seq=5

It's all very long and very detailed and kind of hard to get a feel for in one sitting. For instance, in the passage below, Marx is talking about how gold is used as currency, where it derives its value from, whether it is in itself a commodity and how it empowers private people in private business. He even quotes Christopher Columbus as saying that gold is a "wonderful thing" in a letter from Jamaica dated 1503.

Even if Jean Laffite, who was himself by no means a scholar, had tried to read some of Marx's works in manuscript, he could have read for a long time without encountering anything that sounded the least bit "Marxist."

One of the catch-phrases of Marxism is that workers should own the means of production. But what does that actually mean? And how would it apply to privateering?

It was during the industrial revolution that tasks such as spinning and weaving, which had formerly been performed privately in the home, came to be done in factories by workers who did not own the equipment on which they were working . In the United States, immediately after the War of 1812, many businesses were incorporated and investors contributed funds and received stock in return, for the purposes of textile production. During the Panic of 1819, when the United States repaid to Britain the debt that it owed to Napoleon for the Purchase of Louisiana, many of these businesses went bankrupt or were on the verge of bankruptcy, due to a shortage of specie. But in order to prevent a general economic collapse, instead of allowing all these businesses to fail, the government passed debtor relief laws whose overall effect was to go to fiat currency instead of specie based currency. In the Western territories, confidence in paper money was so low that people went back to the barter system, using whiskey to index the value of all other commodities. Jean Laffite lived through all of that. At the time of his death, he was probably also aware of the extreme conflict of interest between the industrialized northern states, as opposed to the agrarian south.

Jean Laffite used the term "wage slavery", which refers to people who are paid a wage for working in other people's businesses. rather than owning their own business and getting a share of the profits. He expressed in his journal a desire to liberate wage slaves. Marx is known to have written of the extreme tedium and soul destroying monotony of working in a factory as a mere laborer. Jean Laffite's crew members were anything but wage slaves. The work they did was exciting, and they were motivated to work hard because unless there was a prize, they got paid nothing. They were not marking time to earn money by the number of hours that they served. They were paid for results, not for effort!

But does any of that mean that Jean Laffite favored nationalizing the factories and letting the government run them? I don't think so. On the contrary, he probably favored the privateering model, which is one that acknowledged the rights of owners of ships to the greater share of the spoils, but paid each crew member a specified percentage of the take.

Who actually did nationalize all the privateering vessels? In Cartagena. it was Simon Bolivar who did this. The last vessel that Jean Laffite is known to have served on was the General Santander, which belonged to the government of Colombia. There Jean Laffite, for the first time in his adult life, did not own the means of production, but was a mere government employee. In the United States, privateering was greatly curtailed as well, giving rise to a national defense that consisted of both a standing army and a standing navy, and discouraged the private waging of war for profit.

Can any modern day American warrior say that he owns the war machinery that he uses?

Not everything is as it seems. Nationalization actually takes the means of production out of the hands of the workers. Socialism is the very opposite of privateering. And it stands to reason that if Jean Laffite supported Marx's position on the workers owning the means of production, he thought it meant a restoration of privateering in all trades and business, rather more nationalization of ships and factories. Jean Laffite was no Marxist, as that term is currently understood.

And how about Marx himself? I have no idea. I would have to read all his works before I could form a coherent opinion on the matter. But I can tell you this: I have a really strong hunch that he did not want people living off hourly wages. He wanted them to own things.

One of the memes floating around the internet today goes something like this: "Jesus was not a Christian. Mohammad was not a Moslem. Buddha was not a Buddhist. They were just people who had something to say." Is it possible that Karl Marx was not actually a Marxist?