Looking back over poetry from my twenties, I am overcome by its fluency and eloquence. I doubt I will ever write poems quite like that again.

|

There Can Be Gods is a poetry anthology I contributed to in 1989

The cover ilustration is by Linda Holt |

For some people, the idea that as we mature we may lose our abilities to create, while retaining property rights to works made long ago is unacceptable. Those people believe we are not really poets, unless we write poetry all the time. They think it is all in the work and never in the works -- all labor and no product. They think people should be paid a decent wage for the work they do today, instead of a fee for the product they made yesterday. They believe we are valuable to others only so long as we work, and the moment we stop working, we become a burden on society.

Socialists keep saying that we owe a debt to our predecessors and that's why we have to pay taxes to the state, but when it comes to paying royalties or rents or interest on money in the bank, they are against that, because they will not acknowledge our contemporaries' debt to us. "Rent seekers" are bad. "Workers" are good. But what if today's rent seekers are yesterday's workers or their descendants? What happened to the debt to our predecessors? Where did that concept go?

|

| We are born only once. It changes everything. We are never the same after that. And as poets we only ever write about it once. |

We are born only once. We emerge into consciousness only once. We only have one life, and as we sharpen our self-discipline, we lose a certain kind of spontaneity and fluency. It doesn't just happen to poets. I think that it happens to everyone, in one way or another, and if we want to preserve and honor the value of what we have created in our youth, we have to acknowledge that our riper fruit is different. And sometimes not as juicy.

When my first novel,

The Few Who Count came out, most people agreed that it was not quite a mature work. But

The Few Who Count continues to sell a little each year, ever since it came out on Kindle:

The Few Who Count, though by no means a bestseller, does appeal to a

certain readership. Its message about

the corporate entity is as true today as it was then.

I finished writing

Vacuum County in 1993. It was a well-crafted novel, and for years I held out for publication by a New York publisher. Eventually, I gave up, and so it came out in 2012 in time for the 19th anniversary of the Mt. Carmel Massacre. It has seven perfect reviews. And nobody is buying it.

I will never write a book like Vacuum County again, because there is no reason to write Vacuum County again. I said what I had to say there, and then I moved on. Vacuum County deserves a place in literature. But the idea that I should just keep repeating myself by creating equivalent novels is completely unrealistic. That's not how the creative process works. It would be just as wrong as if I got stuck in a loop writing that same perfect poem about birth over and over again. It can't happen. This is not how life works.

Our Lady of Kaifeng is a followup to Vacuum County that readers respectfully accept. It's literary. It's deep. It's meaningful, and it does not mess with anything too sexual or raw or disturbing. It's a deep novel, but somehow it does not ruffle feathers. People write nice reviews or they write no reviews, but nobody is going to be so enraged by Our Lady of Kaifeng that they are going to write something hateful. And nobody is ever going to buy it, either. Unless, of course, my other novels take off.

But in the very middle of writing Our Lady of Kaifeng -- somewhere in between writing Part One and writing Part Two -- something weird happened to me. And I lost some of my respectful readers along the way. Which is okay, because those respectful readers never helped me sell any books, anyway.

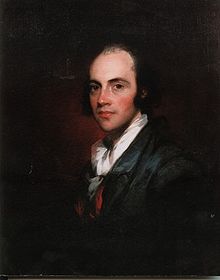

The weird thing that happened was Theodosia and the Pirates.

Novels are not planned. They just happen. Like babies. I mean, they do, if you are lucky. And I consider myself lucky.

This is not imply that any of my novels, critically acclaimed or not, is selling particularly well. But each of them is different, and each was written for a reason, and I am not planning to re-write any of them, nor will I ever write any of them again. Each is a unique experience.

Maybe

The Few Who Count was a little unripe -- a little raw in terms of skill. Maybe

Vacuum County represents the peak of my achievement, and maybe

Theodosia and the Pirates is a bit over-ripe. Perhaps

Our Lady of Kaifeng is mature, respectable fruit that nobody will ever rave about, except those who are hopelessly

intellectual and well read.

I believe that even if I never write again, I have already made my contribution. My task now is to make sure that it sells, because if it doesn't sell, for

society it is as if it never happened. In the same way, and for the same reason, I am not planning to have any more children, or to adopt any more chimpanzees, but I plan to see those in my care into adulthood and into a place where they can have lives of their own and make contributions of their own. I don't need to teach another ape to read and write. I just need to

prove that I have already done this, so that the world may know and learn from my experiences.

There is a time to sow and there is a time to reap, and there is no shame in reaping what you have sown, even if you never plan to sow again. There is a time to work, and then there is a time to get rents and royalties and interest on the work you have already done. It would be very bad for society if we threw away every book that was written or devalued people's nest eggs the moment they retired. Honoring those who came before us includes honoring you and me for our contributions in the past even though we are still alive and not ever going to contribute in quite the same way again. And it also includes allowing us to pass our savings onto our children when our time here on earth is done.

No, an inheritance is not a windfall to the heir. It's a contribution from the dead to the living. And it's a contribution we should be allowed to make to the heir of our choice.