The first American Neutrality Act was passed in 1794. It made it illegal for Americans to wage war on a country at peace with the United States. The thing to consider about this act of Congress is that prior to its passage, it was perfectly legal for an American citizen to wage war on his own against a country that the United States was not at war with. The constitution provided that the Federal government under its commander-in-chief, the President, would not be allowed to wage war unless Congress issued a declaration of war. But all the rights not granted to the Federal government were reserved to the states and to the people. So while the president of the United States was bound to remain neutral in all matters, unless Congress voted otherwise, each individual American was allowed to conduct his own foreign policy.

Take a deep breath and think about what this means. American citizens prior to 1794 were considered autonomous. They could make war on other countries in order to pursue their own interests. And, indeed, many Americans were privateers with letters of marque from foreign countries, such as France, and earning a good living by helping others in their wars against the great international empires such as Britain and Spain.

What happened in 1794 to change all that? In 1794, under the administration of George Washington, the United States signed the Jay Treaty with Britain. The Jay treaty was the brainchild of Alexander Hamilton, and it was hotly contested by the Jeffersonian-led Democratic-Republicans, who feared that this was a return to old world aristocratic tendencies and the rule of tyranny.

The other thing that happened in 1794, which I might as well also mention, was the reign of terror of Maximilien de Robespierre and his Committee of Public Safety in France. After the French revolution, Jacobins had taken over France. It was off with everybody's head and a complete deterioration of all civilized things, including private property.

Britain did not want this general lawlessness to spread to England, and George Washington and Alexander Hamilton agreed. So they decided to tie the hands of American privateers who were still working for France. They also thought this would be a good time to repudiate the American war debt to France, since, after all, that promise was made to the French monarchy that helped to free American Colonies from Britain and not to those lawless Jacobins currently in power.

The Jay Treaty cleared the way for the Quasi-War with France under John Adams, an undeclared war that served British interests and helped the United States renege on the American promise to repay its war debts to France. During the Quasi-War with France, the president of the United States ignored the constitutional provision that required him to get clearance from Congress before starting a war. Meanwhile, the Neutrality Act, far from creating neutrality was used to make sure that no individual American fought for a side in any war that the president did not want him fighting on.

Just like the Committee for Public Safety in France, that did anything but insure public safety, the Neutrality Law was named the very opposite of what it did.

But our subject here is not the Neutrality Act of 1794. Our subject was the Neutrality Act in 1817. The original Neutrality Act was superseded by this new act that also mentioned the unrecognized governments of newly liberated Latin American countries as additional powers that American citizens were not to help anymore. Henry Clay called this an "Act for the benefit of Spain against the Republics of South America." The act prescribed penalties of three years imprisonment and three thousand dollars in fines.

Far from breeding neutrality, all these laws collectively were used to tie the hands of American privateers and to help the great empires of Britain and Spain to hold on to their dominions. But much more importantly than this, the Neutrality Act was used to subdue the independent spirit of American businessmen, who henceforth would need the permission of their government to conduct business abroad and to defend their foreign holdings.

When Jean Laffite was routed out of all his holdings in both Barataria and Galveston, this disempowerment did not happen to him alone. It happened to all Americans, who became more like subjects and less like citizens under a government that took on itself more and more power. In order to pursue its own dreams of empire, the United States government under James Monroe wanted no competition from private citizens in the international arena.

Showing posts with label Neutrality. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Neutrality. Show all posts

Monday, October 6, 2014

Wednesday, April 2, 2014

President Monroe's First Address to Congress

|

| James Monroe by Samuel Morse from the wikipedia |

A similar establishment was made at an earlier period by persons of the same description in the Gulf of Mexico at a place called Galvezton, within the limits of the United States, as we contend, under the cession of Louisiana. This enterprise has been marked in a more signal manner by all the objectionable circumstances which characterized the other, and more particularly by the equipment of privateers which have annoyed our commerce, and by smuggling. These establishments, if ever sanctioned by any authority whatever, which is not believed, have abused their trust and forfeited all claim to consideration. A just regard for the rights and interests of the United States required that they should be suppressed, and orders have been accordingly issued to that effect. The imperious considerations which produced this measure will be explained to the parties whom it may in any degree concern.To obtain correct information on every subject in which the United States are interested; to inspire just sentiments in all persons in authority, on either side, of our friendly disposition so far as it may comport with an impartial neutrality, and to secure proper respect to our commerce in every port and from every flag, it has been thought proper to send a ship of war with three distinguished citizens along the southern coast with these purpose. With the existing authorities, with those in the possession of and exercising the sovereignty, must the communication be held; from them alone can redress for past injuries committed by persons acting under them be obtained; by them alone can the commission of the like in future be prevented.

President Monroe's use of the term "impartial neutrality" belies his assertion that he has the right to "suppress" the establishment at Galveston, when Galveston is outside the territorial claims of the United States at that time. His questioning of whether these establishments were ever "sanctioned by any authority whatever" begs the question by what authority the government of any country, and especially an upstart like the United States, is sanctioned.

To conquer a territory outside your own borders requires a declaration of war against those who hold it. To tell an established government that it must be suppressed is an act of war. You would think that if this is what James Monroe had in mind, he would be asking Congress for a declaration of war against the currently established government at Galveston. Instead, he informs Congress that he has sent a ship of war.

Jean Laffite had a policy engraved in stone not to make war on the United States, whom he regarded as his ally. But the United States more than once made war on him, without a declaration.

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

American Diplomacy in the Wake of War

Diplomacy is just one of the tools of war. At the bargaining table, many a nation has won more territory than it could possibly have conquered in a pitched battle. At the bargaining table, many a victor's gains have been squandered. Sadly, the United States has a long history of dumping friends in order to make "peace" with bullies.

Neutrality would be a very fine thing, if it meant not getting involved in other people's disputes. But under the pretext of maintaining "neutrality" the United States has often broken with its natural allies in order to appease its more powerful enemies.

Can you imagine going to war with France to help Britain, when only a few years earlier France helped you win your independence from Britain? That's what the administration of John Adams did without a declaration of war.

Or how about the way the Soviet Union ended up our ally in World War II and FDR divided up the world between himself and Stalin at Yalta? Was that in the best interest of US citizens? How?

Or the way in which Israel is constantly being pressured to give up territory for the sake of peace, while simultaneously being offered bribes in the form of American financial aid at taxpayer expense? Would a powerful Israel not be a good thing for the US? How does using taxpayer money to bribe Israel not to defend itself from forces unfriendly to the US help American citizens? Does it make the price of oil go down? I don't think so.

Or exactly why was it that we severed diplomatic relations with our friend Taiwan in order to make peace with Mainland China? Wouldn't "neutrality" have demanded that we treat both China and Taiwan just exactly the same? Why do we have to stop being friends with Taiwan in order to offer friendship to China? Would a real friend ever ask that of us?

All of these actions are part of a pattern that was established very early on in the history of the United States. There is nothing new under the sun, except that diplomacy as practiced by the US State Department does not tend to promote the natural interests of the United States and often penalizes United States citizens who are taxed to support policies inimical to their own interests.

The treatment of Jean Laffite by the United States, both at Barataria and at Galveston, is a case in point. Having driven Laffite out of his territory at Barataria when he helped defend New Orleans from the British invaders, when he moved to Galveston where he served as a buffer against Spain the United States went on to demand that he leave again, and not so that United States forces could take possession, either. It was so that Spain could retain its holdings in Texas, and so that the United States could maintain its fragile "friendship" with Spain. Is that neutrality? Siding with the local bully against the underdog who is friendly to you?

This is my take on it. But what did Jean Laffite think? A few well chosen snippets from his journal will give us an idea.

In this section of the Journal, Jean Laffite is talking about the events that precipitated his expulsion from Galveston. They involve the Spanish Ambassador de Onis putting pressure on President Monroe.

Like his father before him, John Quincy Adams, then secretary of state under President Monroe, sympathized with the British. It was a historic preference inherited from his father, the second president. The Federalist John Adams favored Britain, while Democratic-Republican Jefferson had been sympathetic to France. Nobody seemed to be neutral, each faction having its own preferences in the European power struggle. In fact, throughout the career of Jean Laffite, it seems that the struggle between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists, even when it seemingly culminated in the demise of the Federalist party, was still a factor. There are echoes of this in the Journal of Jean Laffite.

Jean Laffite writes:

Concerned that there might be some official sanction behind Graham's words, Jean Laffite set out to Washington, where he met with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. At the time, Adams was fifty-one years old and Jean Laffite was thirty-six. Adams told Laffite that he had not authorized Graham to speak to him or to ask him to clear out of Galveston. Mr Graham was acting alone and without the sanction of the United States government.

Then again, John Quincy Adams can't have been all that taken with Thomas Jefferson or Napoleon, either. It would be amusing to hear with what tone of voice Adams said this.

In the end, when public opinion had been turned entirely against Laffite after the Le Brave incident, and when Graham was again dispatched to tell him he must leave, this time in a more official capacity, Jean Laffite informed George Graham that his government was against England and Spain, and he would abandon Galveston only on the condition the United States would occupy the Antilles as well as Florida. George Graham replied that he was more interested in loans received from Spain than in annexing any of its territories.

Can you imagine someone more interested in the well-being of the United States than one who insists that before he can abandon his post as a bulwark against its foes, the United States should take over more territory?

The story of Jean Laffite should stand as a warning to all external well-wishers of the American experiment, not to set too much store on the friendship of a government whose foreign policy is to neutralize its friends for the sake of doing business with its enemies.

Neutrality would be a very fine thing, if it meant not getting involved in other people's disputes. But under the pretext of maintaining "neutrality" the United States has often broken with its natural allies in order to appease its more powerful enemies.

Can you imagine going to war with France to help Britain, when only a few years earlier France helped you win your independence from Britain? That's what the administration of John Adams did without a declaration of war.

Or how about the way the Soviet Union ended up our ally in World War II and FDR divided up the world between himself and Stalin at Yalta? Was that in the best interest of US citizens? How?

Or the way in which Israel is constantly being pressured to give up territory for the sake of peace, while simultaneously being offered bribes in the form of American financial aid at taxpayer expense? Would a powerful Israel not be a good thing for the US? How does using taxpayer money to bribe Israel not to defend itself from forces unfriendly to the US help American citizens? Does it make the price of oil go down? I don't think so.

Or exactly why was it that we severed diplomatic relations with our friend Taiwan in order to make peace with Mainland China? Wouldn't "neutrality" have demanded that we treat both China and Taiwan just exactly the same? Why do we have to stop being friends with Taiwan in order to offer friendship to China? Would a real friend ever ask that of us?

All of these actions are part of a pattern that was established very early on in the history of the United States. There is nothing new under the sun, except that diplomacy as practiced by the US State Department does not tend to promote the natural interests of the United States and often penalizes United States citizens who are taxed to support policies inimical to their own interests.

The treatment of Jean Laffite by the United States, both at Barataria and at Galveston, is a case in point. Having driven Laffite out of his territory at Barataria when he helped defend New Orleans from the British invaders, when he moved to Galveston where he served as a buffer against Spain the United States went on to demand that he leave again, and not so that United States forces could take possession, either. It was so that Spain could retain its holdings in Texas, and so that the United States could maintain its fragile "friendship" with Spain. Is that neutrality? Siding with the local bully against the underdog who is friendly to you?

This is my take on it. But what did Jean Laffite think? A few well chosen snippets from his journal will give us an idea.

In this section of the Journal, Jean Laffite is talking about the events that precipitated his expulsion from Galveston. They involve the Spanish Ambassador de Onis putting pressure on President Monroe.

Ambassador de Onis protested more violently and thus forced President Monroe to send agents to Texas to verify the settlement of French refugees without the power of General Lallemand and to prevent him from settling in United States territory.

George Graham, who gave himself the honors, was chosen for the mission. Mr. Graham was involved in banking matters in Washington, and he was always ready for placement when the occasion presented itself. Mr. Graham did not sympathize with Luis de Onis.

So then Mr. de Onis protested to Secretary John Quincy Adams on the subject of the French invasion of Texas. Mr de Onis and Mr. Adams were able to come to an agreement on their points.John Quincy Adams, like his father John Adams, sympathized with the British against the French. He was perhaps more nearly neutral about Spanish interests, but Ambassador de Onis knew Adams the younger rather well, and he knew how to manipulate him to see things his own way.

Mr. Adams did not make much noise on the subject of my commune, but when he learned that my corsairs seized British ships, then along with the rest of his cabinet, he protested.

Like his father before him, John Quincy Adams, then secretary of state under President Monroe, sympathized with the British. It was a historic preference inherited from his father, the second president. The Federalist John Adams favored Britain, while Democratic-Republican Jefferson had been sympathetic to France. Nobody seemed to be neutral, each faction having its own preferences in the European power struggle. In fact, throughout the career of Jean Laffite, it seems that the struggle between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists, even when it seemingly culminated in the demise of the Federalist party, was still a factor. There are echoes of this in the Journal of Jean Laffite.

Jean Laffite writes:

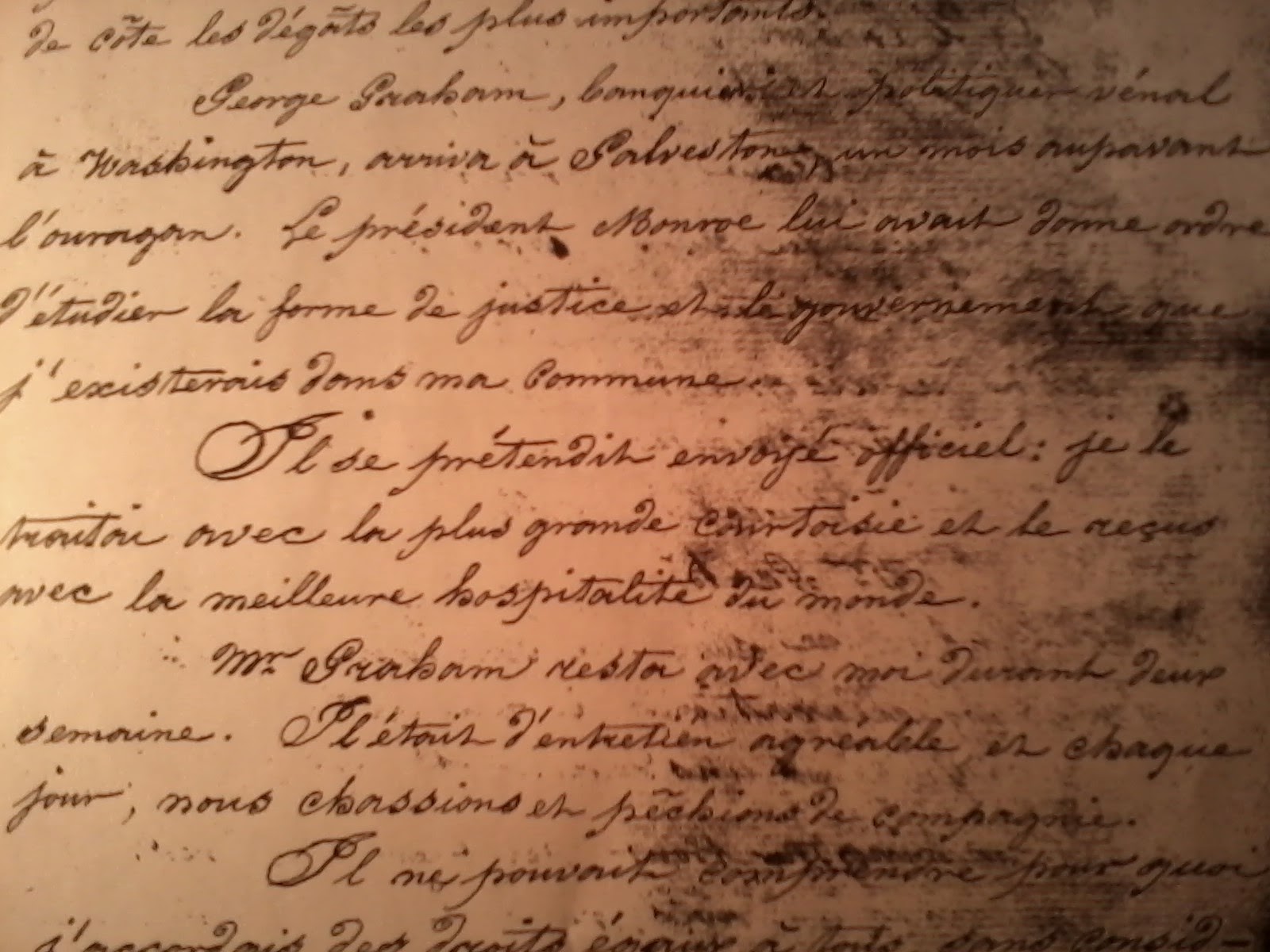

George Graham, a venal political banker in Washington, arrived at Galveston one month before the hurricane. President Monroe had given him orders to study the form of justice and of the government that existed in my commune.

He pretended to be an official envoy. I treated him with the greatest courtesy and received him with the best hospitality in the world.

Mr. Graham stayed with me for two weeks. He was of an agreeable disposition, and each day we hunted and fished together.

He could not understand why I accorded equal rights to all, without considerations of nationality or religion.

He represented exactly the same type as Alexander Hamilton, opposed to the principles of Thomas Jefferson.George Graham told Jean Laffite that "the territory situated to the west of the Sabine River belonged to the United States which had not authorized me to establish a commune of my choice to the west of that river."

Concerned that there might be some official sanction behind Graham's words, Jean Laffite set out to Washington, where he met with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. At the time, Adams was fifty-one years old and Jean Laffite was thirty-six. Adams told Laffite that he had not authorized Graham to speak to him or to ask him to clear out of Galveston. Mr Graham was acting alone and without the sanction of the United States government.

Mr. Adams affirmed that Mr. Graham was in banking, and was interested above all in commercial loans and credit to private businesses and that he liked neither the ideas of Thomas Jefferson nor the system of Napoleon.

|

| John Quincy Adams as painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1818 from the Wikipedia |

In the end, when public opinion had been turned entirely against Laffite after the Le Brave incident, and when Graham was again dispatched to tell him he must leave, this time in a more official capacity, Jean Laffite informed George Graham that his government was against England and Spain, and he would abandon Galveston only on the condition the United States would occupy the Antilles as well as Florida. George Graham replied that he was more interested in loans received from Spain than in annexing any of its territories.

Can you imagine someone more interested in the well-being of the United States than one who insists that before he can abandon his post as a bulwark against its foes, the United States should take over more territory?

The story of Jean Laffite should stand as a warning to all external well-wishers of the American experiment, not to set too much store on the friendship of a government whose foreign policy is to neutralize its friends for the sake of doing business with its enemies.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)