Diplomacy is just one of the tools of war. At the bargaining table, many a nation has won more territory than it could possibly have conquered in a pitched battle. At the bargaining table, many a victor's gains have been squandered. Sadly, the United States has a long history of dumping friends in order to make "peace" with bullies.

Neutrality would be a very fine thing, if it meant not getting involved in other people's disputes. But under the pretext of maintaining "neutrality" the United States has often broken with its natural allies in order to appease its more powerful enemies.

Can you imagine going to war with France to help Britain, when only a few years earlier France helped you win your independence from Britain? That's what the administration of John Adams did without a declaration of war.

Or how about the way the Soviet Union ended up our ally in World War II and FDR divided up the world between himself and Stalin at Yalta? Was that in the best interest of US citizens? How?

Or the way in which Israel is constantly being pressured to give up territory for the sake of peace, while simultaneously being offered bribes in the form of American financial aid at taxpayer expense? Would a powerful Israel not be a good thing for the US? How does using taxpayer money to bribe Israel not to defend itself from forces unfriendly to the US help American citizens? Does it make the price of oil go down? I don't think so.

Or exactly why was it that we severed diplomatic relations with our friend Taiwan in order to make peace with Mainland China? Wouldn't "neutrality" have demanded that we treat both China and Taiwan just exactly the same? Why do we have to stop being friends with Taiwan in order to offer friendship to China? Would a real friend ever ask that of us?

All of these actions are part of a pattern that was established very early on in the history of the United States. There is nothing new under the sun, except that diplomacy as practiced by the US State Department does not tend to promote the natural interests of the United States and often penalizes United States citizens who are taxed to support policies inimical to their own interests.

The treatment of Jean Laffite by the United States, both at Barataria and at Galveston, is a case in point. Having driven Laffite out of his territory at Barataria when he helped defend New Orleans from the British invaders, when he moved to Galveston where he served as a buffer against Spain the United States went on to demand that he leave again, and not so that United States forces could take possession, either. It was so that Spain could retain its holdings in Texas, and so that the United States could maintain its fragile "friendship" with Spain. Is that neutrality? Siding with the local bully against the underdog who is friendly to you?

This is my take on it. But what did Jean Laffite think? A few well chosen snippets from his journal will give us an idea.

In this section of the Journal, Jean Laffite is talking about the events that precipitated his expulsion from Galveston. They involve the Spanish Ambassador de Onis putting pressure on President Monroe.

Ambassador de Onis protested more violently and thus forced President Monroe to send agents to Texas to verify the settlement of French refugees without the power of General Lallemand and to prevent him from settling in United States territory.

George Graham, who gave himself the honors, was chosen for the mission. Mr. Graham was involved in banking matters in Washington, and he was always ready for placement when the occasion presented itself. Mr. Graham did not sympathize with Luis de Onis.

So then Mr. de Onis protested to Secretary John Quincy Adams on the subject of the French invasion of Texas. Mr de Onis and Mr. Adams were able to come to an agreement on their points.

John Quincy Adams, like his father John Adams, sympathized with the British against the French. He was perhaps more nearly neutral about Spanish interests, but Ambassador de Onis knew Adams the younger rather well, and he knew how to manipulate him to see things his own way.

Mr. Adams did not make much noise on the subject of my commune, but when he learned that my corsairs seized British ships, then along with the rest of his cabinet, he protested.

Like his father before him, John Quincy Adams, then secretary of state under President Monroe, sympathized with the British. It was a historic preference inherited from his father, the second president. The Federalist John Adams favored Britain, while Democratic-Republican Jefferson had been sympathetic to France. Nobody seemed to be neutral, each faction having its own preferences in the European power struggle. In fact, throughout the career of Jean Laffite, it seems that the struggle between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists, even when it seemingly culminated in the demise of the Federalist party, was still a factor. There are echoes of this in the Journal of Jean Laffite.

Jean Laffite writes:

George Graham, a venal political banker in Washington, arrived at Galveston one month before the hurricane. President Monroe had given him orders to study the form of justice and of the government that existed in my commune.

He pretended to be an official envoy. I treated him with the greatest courtesy and received him with the best hospitality in the world.

Mr. Graham stayed with me for two weeks. He was of an agreeable disposition, and each day we hunted and fished together.

He could not understand why I accorded equal rights to all, without considerations of nationality or religion.

He represented exactly the same type as Alexander Hamilton, opposed to the principles of Thomas Jefferson.

George Graham told Jean Laffite that "the territory situated to the west of the Sabine River belonged to the United States which had not authorized me to establish a commune of my choice to the west of that river."

Concerned that there might be some official sanction behind Graham's words, Jean Laffite set out to Washington, where he met with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. At the time, Adams was fifty-one years old and Jean Laffite was thirty-six. Adams told Laffite that he had not authorized Graham to speak to him or to ask him to clear out of Galveston. Mr Graham was acting alone and without the sanction of the United States government.

Mr. Adams affirmed that Mr. Graham was in banking, and was interested above all in commercial loans and credit to private businesses and that he liked neither the ideas of Thomas Jefferson nor the system of Napoleon.

Then again, John Quincy Adams can't have been all that taken with Thomas Jefferson or Napoleon, either. It would be amusing to hear with what tone of voice Adams said this.

|

John Quincy Adams as painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1818

from the Wikipedia |

In the end, when public opinion had been turned entirely against Laffite after the Le Brave incident, and when Graham was again dispatched to tell him he must leave, this time in a more official capacity, Jean Laffite informed George Graham that his government was against England and Spain, and he would abandon Galveston only on the condition the United States would occupy the Antilles as well as Florida. George Graham replied that he was more interested in loans received from Spain than in annexing any of its territories.

|

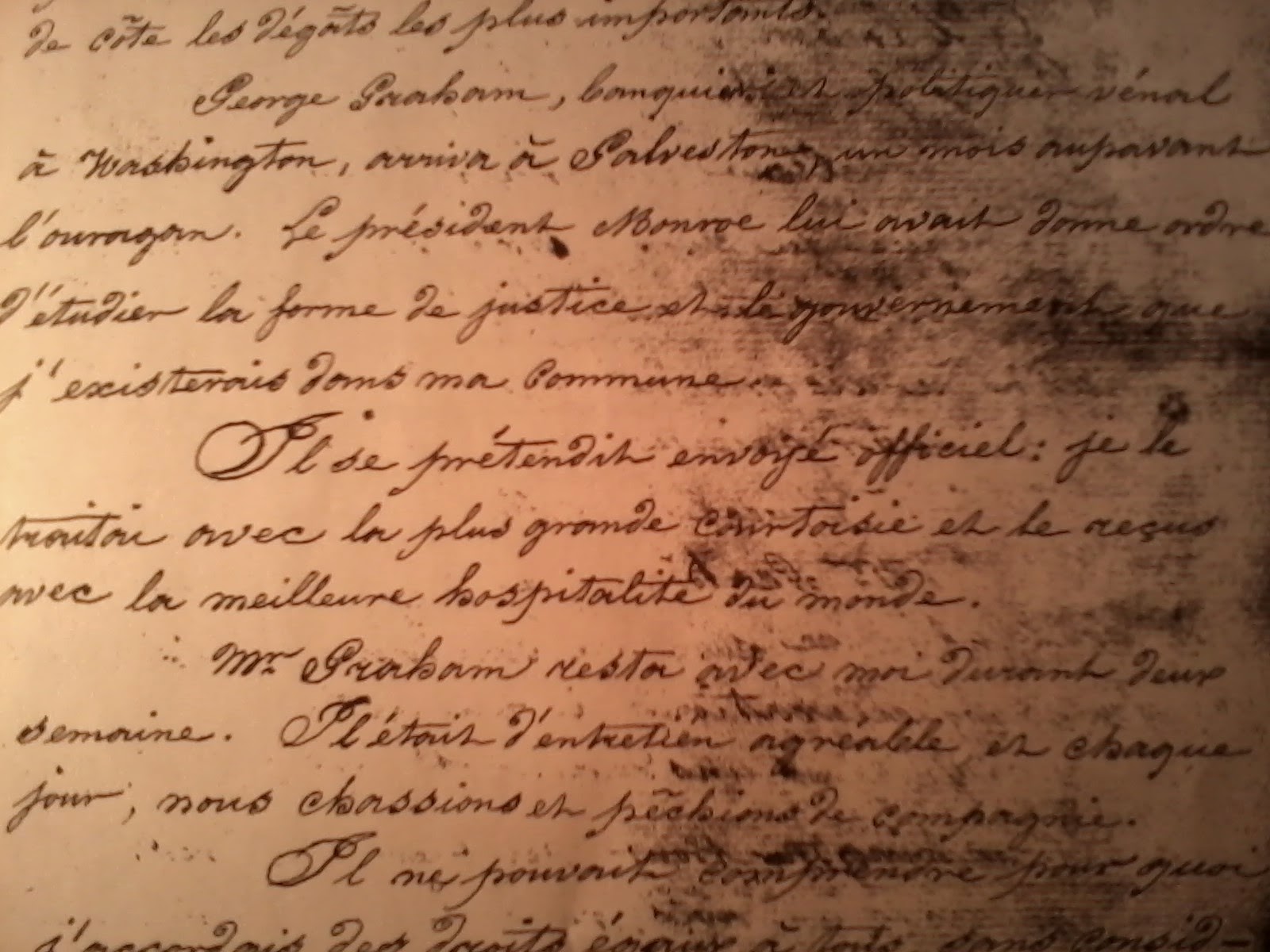

From a page of the Journal that has been badly burned

Relevant text reads: "Nous informames Mr. Graham que notre gouvernment etait contre Espagne et l'Angleterre et que nous abondonerions qu'a la condition que les Etats Unis occuperaient L'Antilles et la Floridie." |

Can you imagine someone more interested in the well-being of the United States than one who insists that before he can abandon his post as a bulwark against its foes, the United States should take over more territory?

The story of Jean Laffite should stand as a warning to all external well-wishers of the American experiment, not to set too much store on the friendship of a government whose foreign policy is to neutralize its friends for the sake of doing business with its enemies.