This is not the first time we have had mixed signals concerning a group of immigrants coming to the United States. Do you know the story of Champ d'Asile?

|

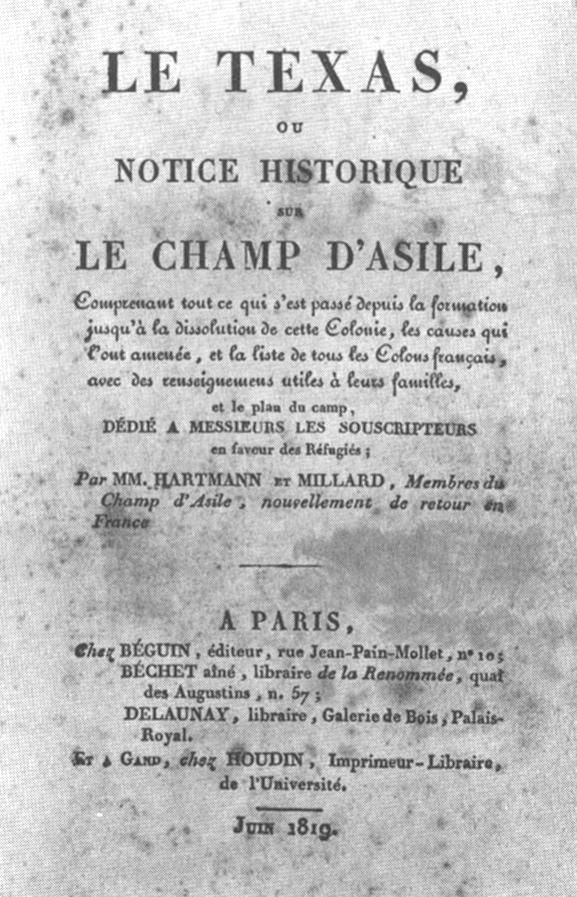

| A History of Champ D'Asile shortly after it was abandoned |

Napoleon had lost his last big battle and was imprisoned for good on the Island of St. Helena. The monarchy in France had been restored. This left a large group of French families, men, women and children, displaced and without a home. They wanted to settle in America. However, when they brought their Society for the Cultivation of the Vine and Olive to Alabama Territory, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, fearing that their true aim was military rather than agricultural, asked them to leave. Having nowhere to go, they searched far and wide for someone who would accept them. The benefactor who allowed them to settle was none other than Jean Laffite.

Jean Laffite welcomed them in Galveston, and there they founded their Champ d'Asile, but its very name a place of asylum. Their experiences included failed crops, encounters with the Karankawa Indians and with alligators and the hurricane of September of 1818. They eventually gave up and were evacuated before the start of 1819.

During the time when the settlers of Champ d'Asile were in Jean Laffite's territory of Galveztown, the privateer assisted them in several different ways. He offered military protection, fortifications and even a grounded battleship to protect them. He also supplied them with some basic nourishment at a time when they might have otherwise starved. Some people think that was generous, and others feel that Laffite did not do enough. In my opinion, what he did was just right.

When a group of people want to join an already existing commune -- and by "commune" I am using Laffite's usage of the word -- they need to offer something of value to the already established people, but they also need to be offered an opportunity to better their own condition. There were no farmers among Laffite's men. They were mostly privateers who made their living off war and commerce. Every country that is going to be viable in the long run needs to make a stab at growing its own food. So it made sense for Laffite to welcome farmers. It made sense for him to offer them protection from those who would displace them, with the understanding that sooner or later they would start to pay their own way by growing their own food and creating a surplus of crops to sell cheaply to the locals. When the French settlers fell on hard times, Laffite even shared his own supplies to keep them alive. But he did not give them enough for them to feel satisfied and for their stomachs to be full. This was a good policy, because it gave the settlers an incentive to keep working for their own subsistence. Laffite also allowed them to come and go at will, and when the settlers deemed their agricultural experiment a failure, they were free to leave.

In every case of legal immigration, as opposed to armed invasion, there has to be incentive on both sides for the inclusion of new people in an already existing settlement. The newcomers must offer some value, and those who welcome them need to understand that the transition might be difficult. But most of all, the experiment of trying to live together must be provisional. If the new people are not happy, they should be free to go. If their hosts are not happy with their contribution, it should also be possible to expel them. Like every business transaction, immigration needs to be two-sided and voluntary. The immigrants should not be imprisoned and kept from leaving, and the populace among whom they settle must be free to decide how much or how little help they wish to give them. Nothing should be taken by force on either side of the transaction.

No comments:

Post a Comment