Yellow fever is a case in point. The following article by Pam Keyes describes how Napoleon's loss of Haiti and his decision to give up Louisiana were almost entirely decided by the immunity to yellow fever of the Haitian blacks and the complete vulnerability to the disease of the French troops sent to put down the rebellion:

http://www.historiaobscura.com/yellow-fever-napoleons-most-formidable-opponent/

Yellow fever was also instrumental in the fall from grace of Edward Livingston. He was holding two offices in New York City, one local and one Federal, when he took sick while attending to his duties as mayor. While he was ill, a subordinate embezzled money from the funds of the Office of the United States Attorney to which President Jefferson had appointed him. Livingston was forced to resign, turn over his entire fortune to the Federal government and try to start a new life in New Orleans. Jefferson never forgave him. However, having survived yellow fever, Livingston was extremely resilient, lived through the War of 1812 as a prominent citizen in New Orleans, and was able to attain to the high federal office of Secretary of State under President Andrew Jackson.

http://www.historiaobscura.com/edward-livingston-a-famous-man-that-few-have-heard-of/

Malaria was another disease that played havoc with unexposed populations, while sparing the adult slaves who could not avoid exposure.

http://www.historiaobscura.com/malaria-in-colonial-america/

In South Carolina during the War of 1812, malaria not only took the life of Governor Joseph Alston's only son, Aaron Burr Alston (Gampy), it also made it impossible for him to maintain discipline in the state militia.

http://www.historiaobscura.com/governor-joseph-alstons-record-in-the-war-of-1812/

Because the rich planters had avoided exposure to malaria by fleeing the area during the hot season, they were spared the high infant mortality that black slaves were exposed to, but they ended up with children who had not acquired immunity to the disease, and as adults were useless for military service in the field. If instead they had allowed their children to be exposed to the disease, then infant mortality would have been higher, but surviving children, and hence military-aged adults, would have been immune.

Immunity to malaria is acquired differently from the way immunity to yellow fever works. In the case of yellow fever, those surviving the disease acquire immunity by antigens in their bloodstream. Infants and persons under the age of five suffer a much milder disease, so that exposure at an early age is beneficial, and infants of mothers who have had yellow fever have what is known as passive resistance.

Immunity to malaria, on the other hand, involves genetic changes through natural selection. Malaria is said to have placed the greatest selective pressure on the human genome -- more than any other disease -- in recent years. Genetic immunity is acquired, among other paths, through the sickle cell trait, which can lead to sickle cell anemia in those who are homozygous -- having two copies of the allele -- but does not lead to anemia in those who are heterozygous or have just one copy. In other words, the trait is recessive and is helpful enough for survival that it remains in exposed populations despite the risk of anemia to some descendants.

|

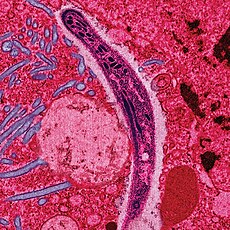

| A Plasmodium, the living entity that malaria consists of |

Whether a population acquires immunity to a disease through antigens or through mutation, the greatest danger to the safety, health and well being of the public can come not from exposure to the disease, but from its complete and total eradication and then an accidental or deliberate reintroduction.

Take the case of the recent cholera epidemic in Haiti. Cholera had been completely eradicated among the Haitians for about a century. As a result, no living person in Haiti had any immunity to cholera. Then in 2010 there was an earthquake. The UN sent in a peace-keeping force that included Nepalese who carried cholera. In short order, one in sixteen Haitians came down with the disease and eight thousand have died of it.

http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2013/01/12/169075448/after-bringing-cholera-to-haiti-u-n-plans-to-get-rid-of-it

One of the benefits of being a first world country may be low exposure to many epidemics. Some people think we should try to eradicate all disease. In doing so, we would be freeing ourselves from the last source of natural selection for our species, as we have eliminated all other predators long since. But one of the dangers of artificial eradication is complete lack of immunity and total helplessness in the face of the accidental or intentional reintroduction of the pathogen.

Today, we have new people, some of them mere children, coming in to the United States through our southern borders, Many of them may have been exposed to diseases that we have eradicated a long time ago. They may be healthy and immune, but our lack of exposure can make us vulnerable. The balanced approach to disease control is to acquire immunity naturally, rather than trusting that we will never be exposed again.